During my commute home this evening, I stopped at the intersection of Constitution and 23rd beside an impeccable 80s-vintage Rolls Royce. I checked out who was behind the wheel - because that's what people behind the wheel of Rolls Royces want - and saw a white-haired baby boomer who looked like he bought the car new with gold bars from the family vault. His windows were rolled down, and I could hear the music he was playing:

Abba.

"Money Money Money."

It's a rich man's world, indeed.

Tuesday, March 27, 2007

Wednesday, March 21, 2007

School dress codes

There's an article in today's San Francisco Chronicle with the headline: "Fighting for the right to wear Tigger." In a nutshell, a 7th-grader landed in detention because her socks did not conform to the school's dress code. On Monday, the American Civil Liberties Union filed suit against the school district on behalf of six students and their parents, claiming that school policy violates their constitutional rights. According to the article:

Or litigation, apparently.

The Napa Valley Unified School District's dress code permits solid colors only, with pictures and logos strictly forbidden. So, naturally, one student considers it perfectly reasonable to wear argyle socks with Tigger on them. That or she doesn't care one wit about the oppressive dress code. I'm betting on the latter.

Someone's obviously itching for a fight, and the parents obviously have little regard for the dress code as well. Why shouldn't my baby be allowed to wear Tigger socks?

Well, there are several reasons. District Superintendent John Glaser has said that the dress code is intended "to ensure the safety and protect the instructional time of all students." The principal of the school in question, Michael Pearson, says "We do not have to deal with issues of kids who are dressing a certain way because their parents are able to shop at the fashionable stores. You cannot tell on my campus the kids that come from a low-income family." They're not alone; the U.S. Department of Education has also supported these views.

I'm with the schools.

People who sue the school district because their child was sent home for violating the dress code infuriate me. These same people probably complain every time their property taxes go up, too, all the while pursuing costly litigation against the school district. Brilliant.

There are better ways to show your disdain for school policies. You want to show The Man you think the rules are ridiculous? The most effective way is to operate within the rules while exploiting their weaknesses.

Personal anecdote time:

I went to a Catholic junior high and high school. Until the 1970s, it was a coat-and-tie establishment. By the time I got there, the dress code had grown lax, requiring little more than casual dress pants and a button-down shirt. In my sophomore year, they outlawed flannel shirts; you can imagine the ire that arose as a result in 1991-92. The next year they tightened the reigns a bit further, but I don't remember how. For my senior year, they reinstituted the requirement to wear a tie.

HOWEVER: They didn't specify much regarding the tie you had to wear. This was probably in deference to Mr. Hall, one of the English teachers, who never wore the same tie twice in a given year. He had a closet in his classroom full of them, including a gag tie that reached all the way to the floor. Not even the administration was going to crack down on this old fossil.

So I made it my mission to wear the most outrageous, hideous ties I could find. Some I found in my dad's closet, and some I bought at the thrift store. For a couple of months straight I wore the same tie, but I modified it every day with various colored markers. One day I burned a hole in it at lunch. My coup de grâce, however, was the day I slipped it over a straightened wire coathanger before putting it on. Throughout the day I could bend it into different shapes. When I walked by the assistant principal with my tie jutting straight out from my chest, I was finally forced to take it off and put on a normal tie. Everyone in the principal's office was laughing, though - even the staff.

Why must righteous indignation always lead to legal action? If students want to fight school policy, then they should do so while demonstrating their ability to function within the system. If parents want to fight school policy, then they should run for the school board or support candidates who share their ideals. Random carelessness is no way to achieve your goal.

Maybe the problem starts at home, not in the schools. In order for my kids to appreciate the flexibility of school policy, I'll just have to make the dress code at home even stricter. Solid colors? Plural? Forget that noise. From this day forward, unless they're heading to or returning from school, all clothing must be black. Head to toe.

They'll look just like Sarah did in high school.

The school's "unconstitutionally vague, overbroad and restrictive uniform dress code policy'' flouts state law, violates freedom of expression, and wastes teachers' and students' time and attention that would be better spent on education.

Or litigation, apparently.

The Napa Valley Unified School District's dress code permits solid colors only, with pictures and logos strictly forbidden. So, naturally, one student considers it perfectly reasonable to wear argyle socks with Tigger on them. That or she doesn't care one wit about the oppressive dress code. I'm betting on the latter.

Toni Kay, now an eighth-grade honors student, said Tuesday that she's been cited more than a dozen times in the last 1 1/2 years, and sent home from school twice

Someone's obviously itching for a fight, and the parents obviously have little regard for the dress code as well. Why shouldn't my baby be allowed to wear Tigger socks?

Well, there are several reasons. District Superintendent John Glaser has said that the dress code is intended "to ensure the safety and protect the instructional time of all students." The principal of the school in question, Michael Pearson, says "We do not have to deal with issues of kids who are dressing a certain way because their parents are able to shop at the fashionable stores. You cannot tell on my campus the kids that come from a low-income family." They're not alone; the U.S. Department of Education has also supported these views.

I'm with the schools.

People who sue the school district because their child was sent home for violating the dress code infuriate me. These same people probably complain every time their property taxes go up, too, all the while pursuing costly litigation against the school district. Brilliant.

There are better ways to show your disdain for school policies. You want to show The Man you think the rules are ridiculous? The most effective way is to operate within the rules while exploiting their weaknesses.

Personal anecdote time:

I went to a Catholic junior high and high school. Until the 1970s, it was a coat-and-tie establishment. By the time I got there, the dress code had grown lax, requiring little more than casual dress pants and a button-down shirt. In my sophomore year, they outlawed flannel shirts; you can imagine the ire that arose as a result in 1991-92. The next year they tightened the reigns a bit further, but I don't remember how. For my senior year, they reinstituted the requirement to wear a tie.

HOWEVER: They didn't specify much regarding the tie you had to wear. This was probably in deference to Mr. Hall, one of the English teachers, who never wore the same tie twice in a given year. He had a closet in his classroom full of them, including a gag tie that reached all the way to the floor. Not even the administration was going to crack down on this old fossil.

So I made it my mission to wear the most outrageous, hideous ties I could find. Some I found in my dad's closet, and some I bought at the thrift store. For a couple of months straight I wore the same tie, but I modified it every day with various colored markers. One day I burned a hole in it at lunch. My coup de grâce, however, was the day I slipped it over a straightened wire coathanger before putting it on. Throughout the day I could bend it into different shapes. When I walked by the assistant principal with my tie jutting straight out from my chest, I was finally forced to take it off and put on a normal tie. Everyone in the principal's office was laughing, though - even the staff.

Why must righteous indignation always lead to legal action? If students want to fight school policy, then they should do so while demonstrating their ability to function within the system. If parents want to fight school policy, then they should run for the school board or support candidates who share their ideals. Random carelessness is no way to achieve your goal.

Maybe the problem starts at home, not in the schools. In order for my kids to appreciate the flexibility of school policy, I'll just have to make the dress code at home even stricter. Solid colors? Plural? Forget that noise. From this day forward, unless they're heading to or returning from school, all clothing must be black. Head to toe.

They'll look just like Sarah did in high school.

Wednesday, March 07, 2007

Free Music Meets Free Market

The other day there was a story posted to Digg about Barenaked Ladies. No, not barenaked ladies - Barenaked Ladies. They're a rock band. If you haven't heard of them, I'm sorry that you've been missing out for nigh on fifteen years. Hard to believe I picked up their first CD half a lifetime ago, but it's true.

But this isn't about Barenaked Ladies. It's about Amie Street, an online music store that just started offering their new album. Like the much better known iTunes Store run by Apple, Amie Street sells music over the web. Amie Street is very much unlike the iTunes Store, however, in two key regards. First, the music is DRM-free, which may or may not be important to you. If you know what DRM stands for, it probably is.

Even more interesting, however, is Amie Street's pricing structure. While 99 cents per song is pretty much the industry standard, all music on Amie Street starts out entirely free. That's right, free. But only to the first customers through the door. As more customers show up to buy a particular song, the price increases gradually, maxing out at 98 cents.

Sound like a revolutionary business plan? It is, and here's why. I've seen a variety of selling strategies before: artists giving away music for free, letting buyers name the price, etc. But Amie Street is unique in the way its pricing structure has the potential to benefit both listeners and artists.

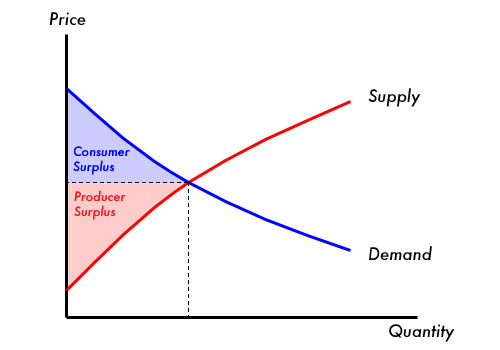

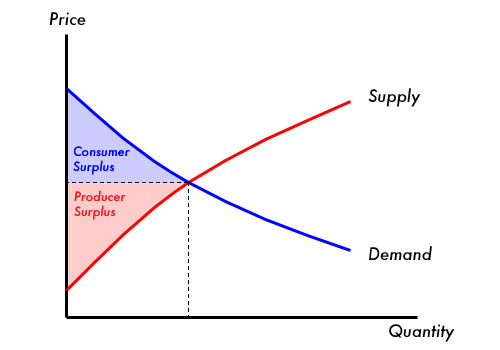

It's all about surplus. Surplus, in economics, is essentially a measure of how well someone made out at the negotiation table. In the world of buyers and sellers, there are always buyers who feel they got a great deal, and sellers pleased with the amount they squeezed out of the buyers. Say the negotiated price for a record is $10. If the buyer went to the table willing to pay $13, then his surplus is $3 - the amount he was willing to shell out but didn't have to. If the seller, on the other hand, would have gone as low as $7 before walking away, then her surplus is also $3 - the amount she got paid above what she was willing to accept. Equilibrium, in the classic sense, is the point at which both sides feel they got a fair deal, but nothing to brag about.

What's revolutionary about Amie Street is the way its model hands all the surplus over to the buyers. Here's a graph of the classic version of supply and demand, with shaded areas showing the surplus:

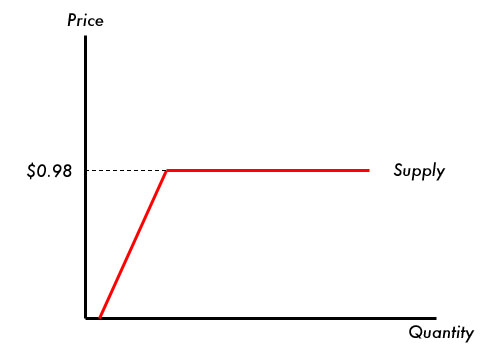

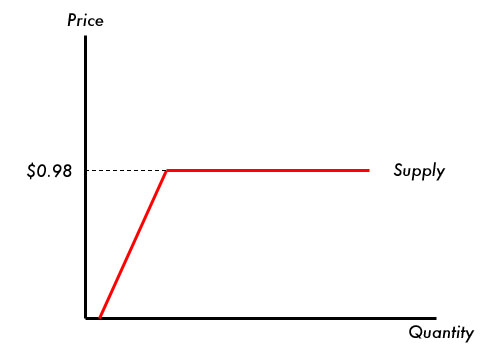

Amie Street's model is different. While I don't know exactly how many songs they will sell at a given price, I imagine their supply curve looks something like this:

Even at a price of $0, Amie Street will sell some number of songs. As the quantity sold rises, though, so does the price. Once the price hits 98 cents, the supply curve plateaus. Why? Because at that price, Amie Street will sell to however many buyers come along. The final sales figure is entirely dependent on demand. The profit is the same for each additional song sold at full price, and Amie Street shares the bulk of the wealth with the artist (70% according to the website).

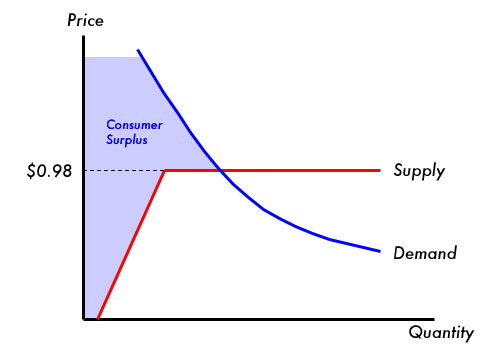

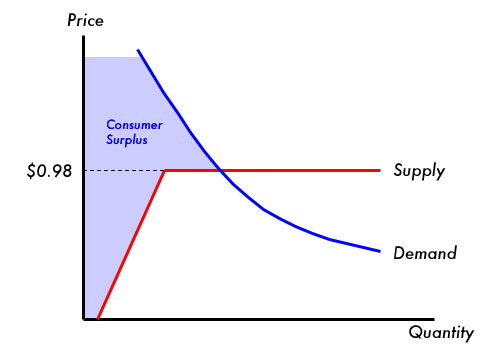

The interesting stuff happens among the buyers. Barenaked Ladies are a popular group; overall demand is pretty high. Within hours of their new songs appearing on Amie Street, the price had climbed to the full 98 cents on all but a few, and all were selling for the maximum price after only a day. The lucky few who bought early made out like bandits: some paid nothing, while many others surely paid far less than they would have otherwise. All that surplus ended up in the buyers' pockets. Amie Street sold each song for exactly what it was willing to accept; there was no surplus whatsoever on the supply side. The graph now looks like this:

All that blue makes for happy buyers.

So that's an illustration of how Amie Street's business model benefits consumers. But why would any rational seller give away all that surplus? Wouldn't Amie Street and the artists who sell on the site make more money if they just started the price at 98 cents? Heck, why not charge twice as much when songs first come out to take advantage of the ardent fans who want the new material as soon as possible no matter what the cost? Turn all that blue to red, and capture the surplus for the seller.

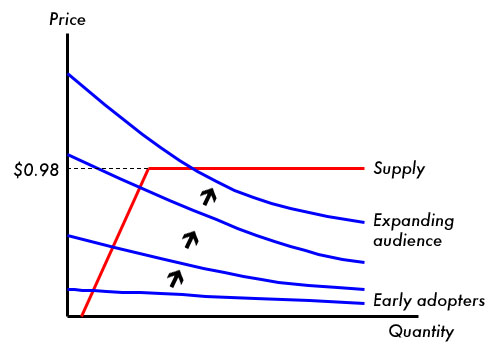

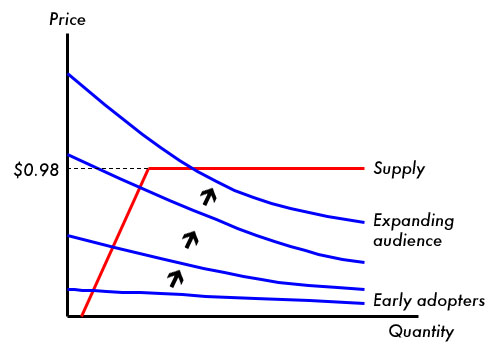

That might work for some artists, especially the most popular ones with the largest fan base. But for others - particularly relative unknowns - Amie Street's model has the potential to grow their market and reap greater rewards in the long run.

See, Amie Street's pricing structure encourages early adoption. That is, by dangling the carrot of free downloads, they encourage buyers to seek out and discover new music. Not everything is guaranteed to be good, but diamonds in the rough certainly stand a better chance of being found. Like a song but don't love it? You might not be willing to shell out 98 cents, but a dime? Sure! It might even grow on you over time, so you recommend it to a friend, who might also like it enough to buy it at a lower price. If the product is good enough, this process repeats, and the fan base grows.

Lots of artists rely on word of mouth to expand their audience, but Amie Street gives them the potential to accelerate the process. It's hard to imagine the obstacles between buyer and seller being lowered much further than offering free downloads over the web; all it takes is a little initiative to bridge the gap. Amie Street's supply curve is always the same, but as the audience grows, demand grows, and the demand curve shifts.

The greater the demand, the higher the sales. Higher sales means more money for both Amie Street and the artist. With enough success, the surplus given away by the seller may be entirely recouped.

If the product is good enough, an artist might ultimately find its songs selling for full price, without any of the marketing and production costs typically spent by major labels. The costs of distribution through Amie Street are almost entirely marginal (per unit rather than a large fixed sum), so it is easier for artists to get their music into the market. Even for Amie Street much of the cost of operation is marginal; bandwidth in particular is a perfect example of a marginal cost.

My gut reaction when I first read about Amie Street was that it was another marketing gimmick. But the more I think about it, the more I think they're re-writing the rules of the music industry. For years there have been questions about the long-term viability of making music, and there have been plenty of losses along the way. Amie Street might have on its hands a practical solution that pleases both buyers and sellers simultaneously. If it catches on, it might be leading a revolution.

But this isn't about Barenaked Ladies. It's about Amie Street, an online music store that just started offering their new album. Like the much better known iTunes Store run by Apple, Amie Street sells music over the web. Amie Street is very much unlike the iTunes Store, however, in two key regards. First, the music is DRM-free, which may or may not be important to you. If you know what DRM stands for, it probably is.

Even more interesting, however, is Amie Street's pricing structure. While 99 cents per song is pretty much the industry standard, all music on Amie Street starts out entirely free. That's right, free. But only to the first customers through the door. As more customers show up to buy a particular song, the price increases gradually, maxing out at 98 cents.

Sound like a revolutionary business plan? It is, and here's why. I've seen a variety of selling strategies before: artists giving away music for free, letting buyers name the price, etc. But Amie Street is unique in the way its pricing structure has the potential to benefit both listeners and artists.

It's all about surplus. Surplus, in economics, is essentially a measure of how well someone made out at the negotiation table. In the world of buyers and sellers, there are always buyers who feel they got a great deal, and sellers pleased with the amount they squeezed out of the buyers. Say the negotiated price for a record is $10. If the buyer went to the table willing to pay $13, then his surplus is $3 - the amount he was willing to shell out but didn't have to. If the seller, on the other hand, would have gone as low as $7 before walking away, then her surplus is also $3 - the amount she got paid above what she was willing to accept. Equilibrium, in the classic sense, is the point at which both sides feel they got a fair deal, but nothing to brag about.

What's revolutionary about Amie Street is the way its model hands all the surplus over to the buyers. Here's a graph of the classic version of supply and demand, with shaded areas showing the surplus:

Amie Street's model is different. While I don't know exactly how many songs they will sell at a given price, I imagine their supply curve looks something like this:

Even at a price of $0, Amie Street will sell some number of songs. As the quantity sold rises, though, so does the price. Once the price hits 98 cents, the supply curve plateaus. Why? Because at that price, Amie Street will sell to however many buyers come along. The final sales figure is entirely dependent on demand. The profit is the same for each additional song sold at full price, and Amie Street shares the bulk of the wealth with the artist (70% according to the website).

The interesting stuff happens among the buyers. Barenaked Ladies are a popular group; overall demand is pretty high. Within hours of their new songs appearing on Amie Street, the price had climbed to the full 98 cents on all but a few, and all were selling for the maximum price after only a day. The lucky few who bought early made out like bandits: some paid nothing, while many others surely paid far less than they would have otherwise. All that surplus ended up in the buyers' pockets. Amie Street sold each song for exactly what it was willing to accept; there was no surplus whatsoever on the supply side. The graph now looks like this:

All that blue makes for happy buyers.

So that's an illustration of how Amie Street's business model benefits consumers. But why would any rational seller give away all that surplus? Wouldn't Amie Street and the artists who sell on the site make more money if they just started the price at 98 cents? Heck, why not charge twice as much when songs first come out to take advantage of the ardent fans who want the new material as soon as possible no matter what the cost? Turn all that blue to red, and capture the surplus for the seller.

That might work for some artists, especially the most popular ones with the largest fan base. But for others - particularly relative unknowns - Amie Street's model has the potential to grow their market and reap greater rewards in the long run.

See, Amie Street's pricing structure encourages early adoption. That is, by dangling the carrot of free downloads, they encourage buyers to seek out and discover new music. Not everything is guaranteed to be good, but diamonds in the rough certainly stand a better chance of being found. Like a song but don't love it? You might not be willing to shell out 98 cents, but a dime? Sure! It might even grow on you over time, so you recommend it to a friend, who might also like it enough to buy it at a lower price. If the product is good enough, this process repeats, and the fan base grows.

Lots of artists rely on word of mouth to expand their audience, but Amie Street gives them the potential to accelerate the process. It's hard to imagine the obstacles between buyer and seller being lowered much further than offering free downloads over the web; all it takes is a little initiative to bridge the gap. Amie Street's supply curve is always the same, but as the audience grows, demand grows, and the demand curve shifts.

The greater the demand, the higher the sales. Higher sales means more money for both Amie Street and the artist. With enough success, the surplus given away by the seller may be entirely recouped.

If the product is good enough, an artist might ultimately find its songs selling for full price, without any of the marketing and production costs typically spent by major labels. The costs of distribution through Amie Street are almost entirely marginal (per unit rather than a large fixed sum), so it is easier for artists to get their music into the market. Even for Amie Street much of the cost of operation is marginal; bandwidth in particular is a perfect example of a marginal cost.

My gut reaction when I first read about Amie Street was that it was another marketing gimmick. But the more I think about it, the more I think they're re-writing the rules of the music industry. For years there have been questions about the long-term viability of making music, and there have been plenty of losses along the way. Amie Street might have on its hands a practical solution that pleases both buyers and sellers simultaneously. If it catches on, it might be leading a revolution.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)